Inside the Heart and Mind of The Brotherhood Diarist

This is the final entry of Ink's weekly column in which he examined the differences between the original Fullmetal Alchemist anime and its re-telling, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood (based on the original manga). To read previous entries, click here.

The following might seem like it comes out of left field, but it’s important to know how, when, and to what degree I initially became involved with the original Fullmetal Alchemist series in order to understand how I distinguish between and admire both series. A little over six years ago (March 2004), my mother succumbed to a protracted battle with her own heart’s resilience. My brother — who though 7 years my elder acted (and to this day still acts) like a 12-year-old — blamed me for pulling the proverbial cord, which I made the decision to do. Raised by our mother alone for the larger fraction of our lives (our parents divorced when I was 6 and he was 13), my brother and I were suddenly left with no parent but an absentee father figure we had learned not to involve ourselves with too much. I took up the reigns as the responsible parent.

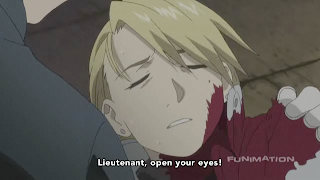

November 2004, just 7 months after the hardest decision I’d yet undertaken in my life thus far, the original Fullmetal Alchemist anime aired on Cartoon Network. It featured closely bonded brothers attempting to defy, via their own grief and skills, the fate that took their mother away. God, how I wanted to be Ed or Al. I wanted that hope. FMA1 gave me that hope by proxy and then exposed me for the fool I was (over the course of the series’ run) for even ever having considered wanting it in the first place ... for being that selfish ... for not accepting the past and moving on ... for not growing despite having been forced to overcome that obstacle and ignorantly forsaking the new point of reference I was inhabiting as home. FMA1 showed me a brother unlike my own, who blindly and stubbornly stuck to his brother’s side and gave him strength through collaboration despite supernatural levels of opposition. And in the end? Those brothers formed a more perfect bond with which to confront the rest of their lives. That storyline struck me to my emotional core, not only as a contrast to the life I had lived but the one I was living as well. It was poetry insomuch as it focused on a singular tragic event and applied it as an extended metaphor, it was overly dramatic and unapologetically so, and everything was image-based (literally visage-based).

I had mixed feelings about the announcement of Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. By the time of its release, I’d more than come to terms with my own emotional involvement with the first series as well as its correlation to my psyche and past. I was also totally content with the first series as a whole, yet interested to see how the second incarnation would differ — having never read the manga from which it purportedly was so exactingly derived (as opposed to the first series). As accepting as I was of my own relation to the characters despite series orientation, as ready as I thought myself to be to reengage a fantastic series about loss and redemption in an entirely different way, as much as I told myself, “this ain’t yo’ daddy’s FMA1,” I found myself, within the first episodes of FMA2, lamenting the lack of retelling of FMA1 — specifically the depiction of loss and solidarity of brotherhood. And then my brain kicked in.

“You’re not in here for the feeling,” it told me, “you’re in here for the storytelling.” And damned if I wasn’t humbled before my own psychoses right then and there. After the initial shock of being denied the depiction of these brothers’ emotional bonds as portrayed in FMA1, I started to accept any and all depicted events as building blocks and discovered them to be the base material of a well-plotted piece of prose portraying a story pertaining to something greater than my selfish self (ahem ... I mean of Ed’s and Al’s selfish selves). As FMA2 continued, it seemed obvious that its focus was not purely emotional. Instead, sociological and political themes took center stage upon a base held aloft by diverse emotional motives.

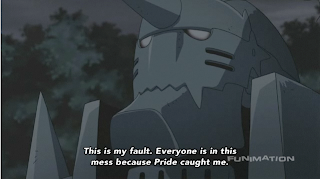

As opposed to FMA1’s chronically dependent, fraternal protagonists, FMA2 builds brothers from a common emotional base, lets them grow for a little while together through shared trials and tribulations, and then divides them for most of the series to become their own stronger selves. No one could poignantly argue that FMA1’s Elric brothers were individualistically portrayed as more three-dimensional characters than FMA2’s Ed and Al (although the strength of an FMA1 Ed/Al hybrid vs. FMA2’s individualistic Ed and Al is intriguing). The grief and selfish struggle of FMA1’s Ed and Al might have been handled more competently than in FMA2, but the overall story was only a fraction of what FMA2 seeks to tell. FMA2 separately presents different circumstances for each bother, who has to confront the various issues at hand without the help of his respective brother (but not without the shared memories of each other’s temperament and rationale).

It could even be said that the strength of supporting characters lends strength to FMA2 by not contributing directly to its main characters. FMA1 relied upon supporting and background cast to do nothing but prop up its own protagonists whenever necessary. FMA2, however, endows Mustang, Armstrong (Alex and Olivier), Hawkeye, and many others, even generic state soldiers, with pertinent background stories that support their influence on the overarching plot rather than the motive of the series’ namesake. FMA2 only focuses on the characters to make a statement about the world, whereas FMA1 forsook the world for its characters. FMA2 is a classic example of animated prose, and a damned fine one at that.

I like Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood far more than I’ve let on in the last 64 diaries, but I don’t particularly identify with it. I don’t believe this is due to any fault of the series other than the fact that one of a similar premise preceded it — one which appeared to me at an optimally influential time and place. That said, I believe FMA2 offers stronger overall character development for most of the cast and excels in manipulating story elements concerning the struggle of humanity vs. non-humanity, while FMA1 provides a more defined inner struggle via its depiction of humanity vs. itself. I’d not blame either for the course it has taken nor the results produced. But I leave you with a totally subjective question. Which is the greater example of artistic competence: the technical aspects behind a work’s execution, or the effects upon its intended audience? The answers are as different as our selves.

Thus has been my love affair with the brothers known as FMA1 and FMA2: 65 weeks of analytical thought, 90 pages of column material, and a greater understanding of both series. I want to thank any and all who’ve read this column and definitely those who’ve commented. If by some slim chance this column was what brought you to Ani-Gamers, I ask you to keep coming back and try clicking through a few of the other links spread around the pages here. We’ve got a great staff with vast insight on a variety of topics I’m sure you’d enjoy, and most know their way around anime and manga a lot better than moi. I also want to thank our editor-in-chief Evan (a.k.a. Vampt Vo) for allowing me to rant every week and for diligently catching any grammatical errors induced by lack of sleep, wine, or both.

News

News Reviews

Reviews Features

Features Columns

Columns Podcast

Podcast