This is a guest post written by frequent Ani-Gamers collaborators Hisui and Narutaki from the Reverse Thieves anime blog. Thanks, guys!

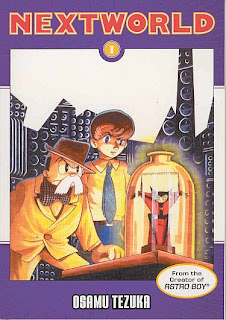

Evan has dedicated the month of March on Ani-Gamers to the legendary "God of Manga" Osamu Tezuka, and while several of the writers at Ani-Gamers are contributing their thoughts and reviews, we at Reverse Thieves heeded Evan's call for guest posts as well! But what to do proved a little difficult; another review wouldn't be much help, so when Evan suggested an essay about some aspect of Tezuka, that really got us thinking. One of the artist's most famous aspects is what is lovingly referred to as Tezuka's Star System, in which his characters appear over and over in again in various works. This has become a unique trait to Tezuka that has gone on to influence a world of manga in various ways.

The Star System is a device that Tezuka uses to have characters appear in similar roles from series to series with the same character design but different names. A character like Duke Red will almost always be a villain, whereas Higeoyaji (a.k.a. Shunsaku Ban) might play a wide variety of middle-aged man roles. Tezuka often remarked on the system and likened it to a director reusing the same actors again and again after finding he liked their performances. Considering Tezuka's nigh-obsession with film and the theatre, and his frequent exposure to these media at a young age thanks to his parents, there is little doubt that they went on to not only inform the way he drew comics, but also the way he saw his characters.

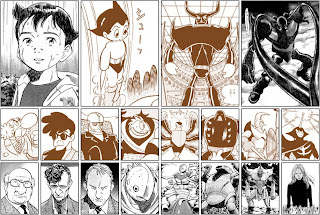

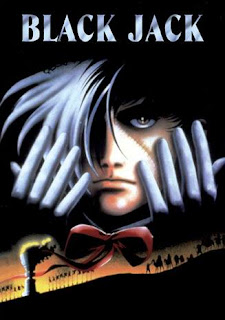

At first you may think this is just a cleverly disguised way of recycling character designs, but it goes deeper than that. Ask most any writer and they will tell you that their characters are often very close to their hearts. Even take a look at yourself and how attached you may become to a character during the course of the story. There is a personal connection that occurs when someone creates a character, a history, and a story for them and Tezuka was no exception; in fact he might have felt it more strongly than most. Tezuka even went as far as writing up lists of the various "actors" he used in his Star System, with notes like how much each was paid. Tezuka fans love the Star System since it rewards readers for reading multiple series, giving them a silent wink and a nod when they notice Star System characters. It is a delightful reward when you spot, say, Rock Holmes in both Black Jack and Astro Boy.

As the "God of Manga," Tezuka's influence can be seen on almost all aspects of manga and anime, and this includes other people using the Star System. While Go Nagai would go onto influence manga in innumerable ways himself, you can see the traces of the Star System in his own manga. Numerous characters from The Abashiri Family and Harenchi Gakuen reappear in Go Nagai's Cutie Honey. Violence Jack is not only a sequel to Devilman but Go Nagai also repurposes characters from several other series for it. You can also look to the prolific Rumiko Takahashi's stories for nods to the Star System. Takahashi has stated that her main character can be seen as the same character viewed during different parts of his life from a child to a young adult.

The Star System also plays a big role in Naoki Urasawa's work. Urasawa makes no bones about him being a huge fan of Osamu Tezuka — made even more clear by his writing of Pluto — but long before that he was taking cues from the Star System. He almost always uses a character that looks like Kosaku Matsuda or Yawara Inokuma in his series as well as several other recurring actors. The Star System reaches beyond manga too, as some anime directors can even be seen using it. Yasuhiro Imagawa is famous for plucking characters from many of the creator's sources when adapting a manga into anime. In Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood Still, not only does he re-imagine Mitsuteru Yokoyama's classic, but he practically turns it into an homage as he pulls characters from Outlaws of the Marsh and Romance of the Three Kingdoms into the story. Imagawa went on to bring a similar feeling to Go Nagai's Shin Mazinger Shogeki! Z Hen.

It is easy to mistake someone using the Star System for an inability to vary their character designs. Although some manga-ka (Ed. note: manga artists) use the Star System, it is hardly a universal staple of the world of manga. At times it might seem that a manga-ka is using the Star System but in is in fact just reusing character designs due to lack of ability, laziness, or time constraints. Much like the difference between homage and rip-off, it can be a tricky matter to determine which is going on without the manga-ka commenting one way or another. But it can also be a fun and insightful line of conversation, because it is no secret that Tezuka's influence runs quite deep indeed.

This is merely an introduction and light examination of Tezuka's Star System. The system itself is more complex and its influence more far-reaching than this simple overview could give. If you wish to learn more about the Star System, you should track down the following books for more information about Tezuka himself and the many unique and influential traits of his manga:

You can also check out the following web sites, which are great resources for learning more about Tezuka:

News

News Reviews

Reviews Features

Features Columns

Columns Podcast

Podcast